001: Introduction & distal tibial fractures

Welcome to our first ever podcast!

Pete and Kash run the Orthopaedics Masters (MSc) at Queen Mary University of London. This can be found on twitter @orthomasters

They both work at The Royal London Hospital, which is part of Barts Health NHS Trust. However, this podcast is nothing to do with the hospital or the university, and they have no affiliation with it whatsoever…

LISTENER CAUTION:

Please be aware that Pete can use naughty language occasionally, and we hope this does not cause any offence. Please listen at your own discretion.

The podcast at this point has no name- Pete suggests the ortho podcast, Kash suggests ‘see one/ do one’, ‘send for the next’, or ‘in the coffee room’!

A bit about us:

LISTENER CAUTION:

Please be aware that Pete can use naughty language occasionally, and we hope this does not cause any offence. Please listen at your own discretion.

Pete Bates - @petebates

BOTA Trainer of the Year, married wearing a toga, and has an eye for designer handbags. He defines himself as an orthopaedic trauma surgeon - ‘a guy who fixes fractures!’ He mainly sticks to the lower limb, but says he can fix a proximal humerus, or an elbow, and may even sneak a wrist fracture fixation in every now and again! His practice is generally around pelvis and acetabular surgery and lower limb trauma. He enjoys polytrauma with patients with multiple injuries who are systemically messed up (yes that’s a technical term).

Why no elective orthopaedic practice?

Pete has never found an elective orthopaedic operation that he really enjoys. He did hip replacements, and reports that they are all fine, and that not all of them are limping! He tried knee replacements too, but found that they never really interested him. He found a lot of this surgery repetitive, causing him to get frustrated. Pete enjoys the immediacy of trauma and describes it as a street fight - being unpredictable, and each case has a little bit of excitement which is never quite as you would want it.

Kash Akhtar (twitter @kashakhtar)

Kash is a Senior Lecturer in Medical Education and specialises in knee surgery. He is a consultant orthopaedic surgeon and part of the major trauma on-call service at Barts. Kash has worked at the Trust for five years and notes that his trauma has increasingly drifted to injuries in and around the knee. Kash likes to think it is because he is good at it, but acknowledges it may just be to keep him away from all of the other joints!

Kash and Pete discuss that in the UK (and across the globe), orthopaedic trauma is increasingly being managed by surgeons with a sub-specialty interest in their respective fields. The role of the generalist is still there but nowadays less so, particularly in the level 1 Major Trauma Centre settings.

Kash has done a Masters and an MD in Medical Education and a fellowship in Education, Leadership and Management. He then did a fellowship in knee surgery at Oxford, and a Winston Churchill fellowship in the United States.

Kash is also the Training Programme Director for the Royal London Rotation, which he likes to think is the UK’s premier rotation!

‘pod cast objectives

The aim for the podcast is to talk about stuff that affects daily practice and life, in a short and digestible format that is easy to listen to such as on a commute. It will probably be linked to the masters to some degree, and there will be special guests from time to time who bring something extra.

Kash and Pete talk about the Miller ‘audiotapes’ and how useful they found them in their training.

Distal tibial fractures:

Pete was asked by Kash to talk to the Royal London and Percivall Pott rotation registrars and consultants on the topic of, “How TF do I get out of this!”

Pete interpreted this is what are the common scenarios when people get stuck during an operation and then they cannot proceed. The “is this ok or should I take it all down and start again” moment. We all have them!

FixDT - Fixation of Distal TIbial Fractures - Plate vs IM Nail

Kash’s interpretation of this study is that IM nails did better early on, but at 6 months there was no real difference in terms of disability. Going into the study, Kash expected the nails to weight bear and mobilise earlier, with plates having a higher infection rate and reduced ankle ROM.

Pete’s goes off on a tangent slightly and talks about RCTs and how these build knowledge, provide a basis for funding for future research, and guide further research. They provide the data for meta-analysis also. We therefore rely on RCTs to guide our practice and they are influential in national guidelines.

It's clear that our own interpretation of the study results are coloured by our opinions or biases prior to the study.

Pete thought that IM nails would be far superior as patients are able to weight bear earlier. This is because IM nails are on-axis fixation devices (down the axis of the tibia), whereas plates are cantilever fixation devices (off axis -down the side of the tibia). Therefore a nail has a mechanical advantage over a plate used in relative stability mode and therefore patients can weight bear earlier.

The actual FixDT trial results showed nails to be significantly better at 3 months, but despite a small difference this was not significant at 6 months or 12 months. Often in orthopaedic trauma studies the long-term results may not be significant as, assuming the injuries go on to union and patient have a normal return of function, the differences between similar treatment strategies can be small.

Pete expected to see a bigger difference and thinks this may possibly be due to the study being potentially underpowered (321 patients). RCTs now (especially those coming out of the US) are tending to have greater numbers of patients in them. This is also driven by funding bodies pushing surgeons to go for bigger numbers in the >1000, such as those by the likes of Mohit Bhandari, JAMA - health trial etc. It is known that as the number of patients in the studies increases the more reliable that data becomes, and an effect or difference can become apparent as the number increase.

UK research is currently quite exciting with many well-designed trials such as the DRAFT and PROPHER studies, and many more, giving us answers to specific questions to help guide treatment and develop guidelines.

Anyway back on topic...

How not to cock up a distal tibial fracture fixation:

So if we are going to use an IM nail, there are still technical challenges to overcome. Improvements in implant design such as multiple plan distal locking screws and the introduction of suprapatellar nailing techniques, make the operation more reliable.

Kash asks Pete if he still does any infrapatellar nailing? Pete says he likes to keep his hand in by doing them as the need may occasionally arise. However he acknowledges that the main indication currently seems to be due to the suprapatellar sets having already been used / have a hole in the packaging etc. Pete feels that infrapatellar nailing is inferior to suprapatellar nailing.

Intra-articular extension:

Distal tibia fractures are often a short spiral and can occasionally extend down into the tibial plafond. If this is the case it is usually non-displaced and assuming that you recognise it and fix it, it doesn’t usually affect the complexity of the tibia nailing.

Distal third tibial fractures often extend into the metaphysis. This is important as this part of the tibia becomes wider. Therefore the nail does not have as much control in this here compared to in the shaft, where it is tightly controlled at the isthmus and the main challenge is to ensure the rotation is correct.

When to CT?

Have a low threshold for CT if there is any suspicion of intraarticular extension. The aim of is to map out the extension to plan exactly where to place a screw to fix it, and prevent it exploding during IM nail insertion. Pete and Kash advocate fixing this early in the procedure to then be able to carry on safely with the rest of the tibial fixation. When doing this one must be mindful to place the screws out of the path of the nail!

How to avoid a valgus malreduction?

We have all seen distal tibial fractures fixed with a valgus malreduction.

Proximally we talk about the importance of the entry point for the nail. This helps decide what the overall alignment and orientation of the nail is. However, in distal tibial fractures this matters much less, as the shaft lies between this and the distal block and will deflect the nail (assuming an acceptable entry point)…. Therefore, whilst the entry point proximally is still important, the key in these distal fracture is where the tip of the nail ends up.

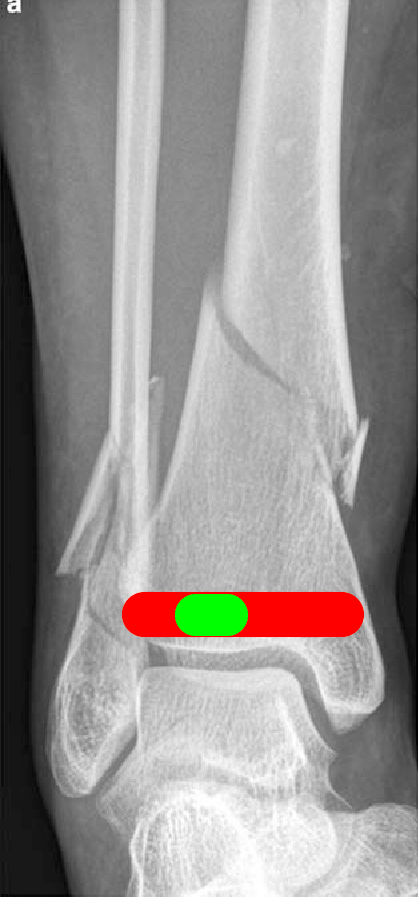

Classically it is taught that the tip of the nail should end in the middle of the tibial plafond. But in these fractures the tibia ‘wants’ to go into valgus, which means that the nail will head down the medial side towards the medial malleolus

(on this x-ray you can see a medialised nail with resultant valgus deformity at the fracture site).

The key to distal third tibial fractures is therefore to put the tip of the nail just lateral to the centre of the tibial plafond. Therefore when nailing a distal third tibial fracture, if the nail ends exactly in the right spot- just lateral to the midpoint of the tibial plafond- it is 99/100 likely that the alignment will be absolutely spot on, without the need for a poller screw or blocking wire.

Kash likes to visualise this as the nail is coming down and imagine reducing the distal block with the metalwork in situ and thinking where would I like the nail to end up, and then place the guidewire there. He then describes that if the wire is there (just lateral to the centre point of the tibial plafond) then as the nail goes down it will reduce the fracture for you.

Pete’s Top Tips!

Pete suggests not to ream beyond the fracture into the articular block- stop reaming once the reamer finishes chattering as it passes the isthmus of the bone into the metaphyseal flare. This prevents the wire getting dislodged and being pulled out. Pete does not think it is critical that the wire is in the correct place in the distal block (just lateral to the centre part of the tibial plafond) at this point, whereas Kash prefers to fix it in the correct spot.

Pete advocates inserting the nail to the level of the fracture site and just beyond. Once the tip of the nail in the distal fragment, remove the guidewire!

Then it’s a fight - you and the nail vs the fracture!

You stand at the bottom end and hold the distal fragment reduced, making sure that the tip of the nail is pointing to the magic point (just lateral to the centre part of the tibial plafond) under the image intensifier. This may require a varus force across the fracture.

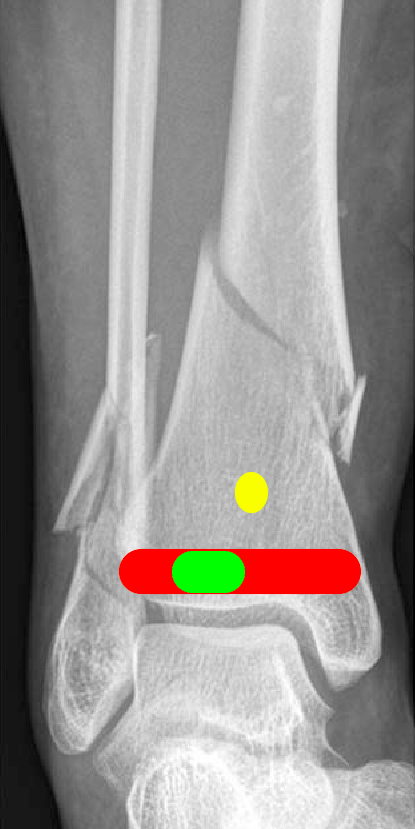

Someone else at the top end gentle taps the nail down, checking intermittently on x-ray to ensure the nail is heading just lateral to the centre point of the tibial plafond (see image on the right).

Check the AP as well as a lateral image to make sure it is heading dead centre to the arch of the ankle joint.

Blocking/ poller wires and screws

Kash points out that Pete may have superhuman powers of anatomical reduction, however many of us may require the assistance of blocking / poller screws or wires.

Pete acknowledges that he does sometimes need the help of a blocking wire. However, he prefers to use a blocking wire as this allows him to be able to adjust the position of it if it's not quite right, or for fine tuning the reduction. For this we often use the entry guidewire. When using a screw use the locking screws from the nail system, but remember these are less forgiving and the positioning of them has to be absolutely perfect.

Imagine if there is a valgus malreduction, the nail is going to want to go down the medial side of the tibia. In order to correct this you would need to move the nail across to the magic point - just lateral to the centre point of the tibial plafond.

Unfortunately you cannot just shift the nail within the tibia bone block and lock it there. To relocate it you need to back the nail out, and place a blocking wire on the medial side of the wire / nail to deflect the nail off laterally and tip the tibia back to a normal alignment. This poller wire or screw should go approximately 1 inch above the tibial plafond, bicortically, in an anterior to posterior direction just medial to the centre point of the tibial plafond (see yellow oval on the image on the left). Then the nail should be passed back down and past the poller wire to reduce the fracture.

If the tibia is still in valgus, or that the nail will not pass the wire, don’t panic! The nail can be backed out, the wire can be adjusted to a better position, and the wire passed back down again to ensure a perfect reduction.

Locking Screws

Once there and anatomically reduced you need to lock the nail. This needs to be done in two planes, you can do one medial to lateral and one anterior to posterior.

Perfection vs revision

It has to be perfect, do not accept it if it’s not quite right. It is human nature to say it’s good enough, but the time to correct deformity is at the time of the primary fixation. The patient should not leave the operating theatre until it is perfect.

Valgus of the distal tibia is poorly tolerated by the patient. Yes it will unite, yes they will walk again, but valgus deformity in the ankle will lead to pain in the ankle, along with problems up the kinetic chain into the knee, hip and spine. Delayed revision surgery is even more challenging, as is the removal of the metalwork and associated morbidity of such procedures (more on this in the next podcast!)

Pete says, just do an awesome operation first time round then nothing more needs doing!

Get it right the first time!

We hope you enjoyed the ‘pod cast! Message us on twitter @kashakhtar and

@petebates with any feedback, questions or suggestions for future episodes.

Kash and Pete